This article originally appeared in Turf Magazine

Landscape Trends: Introducing Regenerative Lawn Care

BY: DANIELLE BURROWS

What happens when property owners want fewer chemicals on their lawns or if an area enacts a ban on synthetic pesticides? As any turf professional can tell you, it’s complicated.

Historically, there have been limited alternatives to chemical fertilizers and pesticides that still meet customer expectations. “A lot of property owners who go organic on their lawns come face to face with organic growing’s limitations,” comments Nate Clemmer, founder and CEO of Branch Creek, a PA-based company developing cleaner turf growing solutions. “They’re spending more money, yet seeing more weeds.”

In addition to less than ideal results, not all organics are as safe as one would like to think. Clemmer says many people “struggle with the confusing… language. Often the word ‘organic’ is more of a marketing effort than a true promise of integrity. Just because a product says it’s organic doesn’t necessarily mean it’s safe for people, pets, and the planet.” Certified organic was coined by the USDA for crops, so it doesn’t apply perfectly to lawn care, he explains. “Because no regulation exists to keep lawn product manufacturers from hijacking ‘organic’ and using it on products, many do, even though most ‘organic’ turf products ingredients don’t come close to certified organic standards,” he adds.

Soil Is The Solution

Despite being an experienced landscaper, Justin Shield, co-founder and director of operations for NJ-based Organic Green Lawn Solutions, also encountered confusion regarding organic options several years ago when pondering safer options for his yard after his daughter’s birth. He went down an admitted “rabbit hole” of research, looking for effective alternatives—and coming up empty-handed. “I couldn’t find one company I’d want to hire for my own yard—a transparent company looking out for the health of our community or ecosystem. Some claimed they did, but when I got on the phone with them, I’d discover they were using the same chemicals as everyone else.”

At the same time, Shield gained some unexpected insight at work. “I had a longtime customer whose yard had started to decline,” Shield recalls. “My boss [at the time] encouraged me to load it up with fungicide and pesticides. Basically, to upsell.” He adds, “The client opted for compost instead. When I came back six weeks later, the difference was like night and day. The biological act of composting had corrected the soil issues and allowed the lawn to course-correct.”

Shield also took continuing education courses, where he encountered instructor Mike Reed, director of Landscape Education with Branch Creek. “Mike is a staple in the turf care industry, and he made an impression on me. He always said, ‘Let the soil do the work for you. If you feed the soil, the plant will do well on its own.’”

“[When turf struggles, most people] don’t realize that the real culprit is actually their lawn’s depleted soil,” says Clemmer. This depleted soil, also known as urbanized soil, is the non-native soil surrounding any home or building—whether constructed last month or last decade. Some green industry experts categorize depleted soil as dirt, which is dead, versus soil, which is alive.

According to “Understanding Soil Microbes and Nutrient Recycling” from Ohio State University Extension, “There are more microbes in a teaspoon of soil than there are people on the earth. Soils contain about 8 to 15 tons of bacteria, fungi, protozoa, nematodes, earthworms, and arthropods.” This living soil creates a sustainable loop that naturally supports healthy plants. To put it simply, plants pull carbon from the air and convert it to carbohydrates; these carbohydrates then feed the microorganisms; the microorganisms create healthy soil; the soil then feeds the plant.

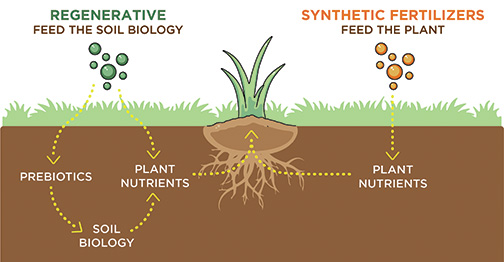

“Traditional lawn care is economical because it’s a trade-off,” explains Clemmer. “Chemical fertilizers behave like an IV, sidestepping soil and funneling nutrients directly to the plant. Over time, the chemicals kill much of the biology in the soil, impeding its ability to release nutrients. At this point, the plant is largely dependent on chemical fertilizer because the natural biology in the soil is no longer capable of effectively supporting growth.”

As a result, “most lawns in America are depleted or close to depleted,” says Clemmer. “Once this happens, it’s not as simple as shifting to fewer chemicals, because there are limited nutrients left in the ground to support new growth.” Essentially, treating soil to support turf can become a self-sustaining cycle.

The Regenerative Movement

Bringing this depleted soil back to life so that it can eventually be maintained using fewer chemical inputs is the backbone of a system called “regenerative growing.” The goal of regenerative growing is to restore soil to the extent that it not only requires few or no chemical inputs but also pulls carbon from the atmosphere—a significant step toward abating climate change.

The regenerative movement started in agriculture. The Rodale Institute and Kiss the Ground are two organizations training farmers on the power, potential, and feasibility of regenerative growing.

Clemmer learned about regenerative practices when researching safer growing alternatives. Similar to Shield, Clemmer was a married father in 2015 when he looked at the creek flowing through his backyard and realized: Everything that goes on my lawn goes into that water. Clemmer’s family had been in the ag industry since the 1860s, starting in feed mills before transitioning to manufacturing chemical fertilizers. Yet he, too, was stymied as to effective alternatives.

As he learned about regenerative growing, he saw its power and promise and thought: Why not apply the same principles to turf? “Lawns comprise far fewer acres of land than agriculture, but if you add up all of the lawns and golf courses in America, it’s nonetheless a significant amount of acreage. By applying regenerative growing to lawns, we can do our part in the cracks and crevices, weaning one lawn at a time off of synthetic inputs and ultimately creating change.”

Clemmer and his team at Branch Creek, including Reed, began developing a system for soil diagnosis and regenerative products. The process starts with a soil test to determine what it contains, what it needs, and what it can biologically handle. While traditional soil tests only measure the amount of nutrients, Branch Creek’s test offers a complete biological profile—a window into soil’s ability to host the microorganisms the way nature intended.

Soil receives a score between one (completely depleted) and seven (healthy). Test results then dictate a customized plan for weaning turf off chemical herbicides and pesticides and moving the lawn closer to a score of seven. “Most urbanized soil scores somewhere between a one and three to start,” Reed explains. “Intervention for these lawns includes safest-in-class pesticides and fertilizers that restore basic health and nutrients.”

Once destructive pests are controlled and soil is brought to a better baseline, the key element of a regenerative process is building back natural organic matter and microorganisms, then feeding those microorganisms. Organic matter can be introduced any variety of ways, such as spreading a thin layer of compost; microorganisms can be fed with simple molasses to sophisticated prebiotic humic acids. The idea is to restore the soil’s biology, where air, plants, and microorganisms support one another as intended. “No one is using fertilizer in the woods, and the woods look great,” Reed points out.

Eventually, as a lawn is weaned off synthetics and a healthful balance is restored, nature can be the primary sustainer.

More Than Green Grass

This living soil offers a great built-in benefit besides low maintenance turf: it has the ability to help reverse climate change. “Healthy, restored soil acts like a sink or a sponge,” Reed explains. “When the grass plant is photosynthesizing, it pulls carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere and stores it in the soil, where it belongs. By comparison, depleted soil has very little storage capacity, or carbon sequestration, which has contributed to our current climate problems—and again speaks to the critical importance of building organic matter.”

For Shield, using regenerative principles on his own property brought results. “My yard wasn’t the best-looking yard on the block, but it was among the better-looking ones, and only required three applications a year. Above all, it was safe for my daughter, which was the most important factor for me.”

Shield also recalls a moment back in the early 2000s, when he first started working in lawn care. He mentioned the job to his grandfather, who opined, “Do you know you’re poisoning the earth?”

“His words stung,” Shield recalls. “He said to me, ‘Mother Earth gives you everything you need to grow.’” Now Shield is putting his grandfather’s philosophy into practice. “Among our unwavering principles at Organic Green Lawn Solutions [an arm of Down to Earth Landscaping] is our transparency. I encourage people to find out what’s being used on their lawns,” says Shield. “I could 100% see regenerative growing becoming the new normal… In the face of state and local restrictions about pesticides and growing concerns about toxins, property owners are clamoring for new lawn care programs that keep yards looking great without the chemical load of years past. This is it.”